CARIBBEAN

Creole languages of the Latin American Caribbean

(Cuba, Dominican Republic, Panama & Colombia)

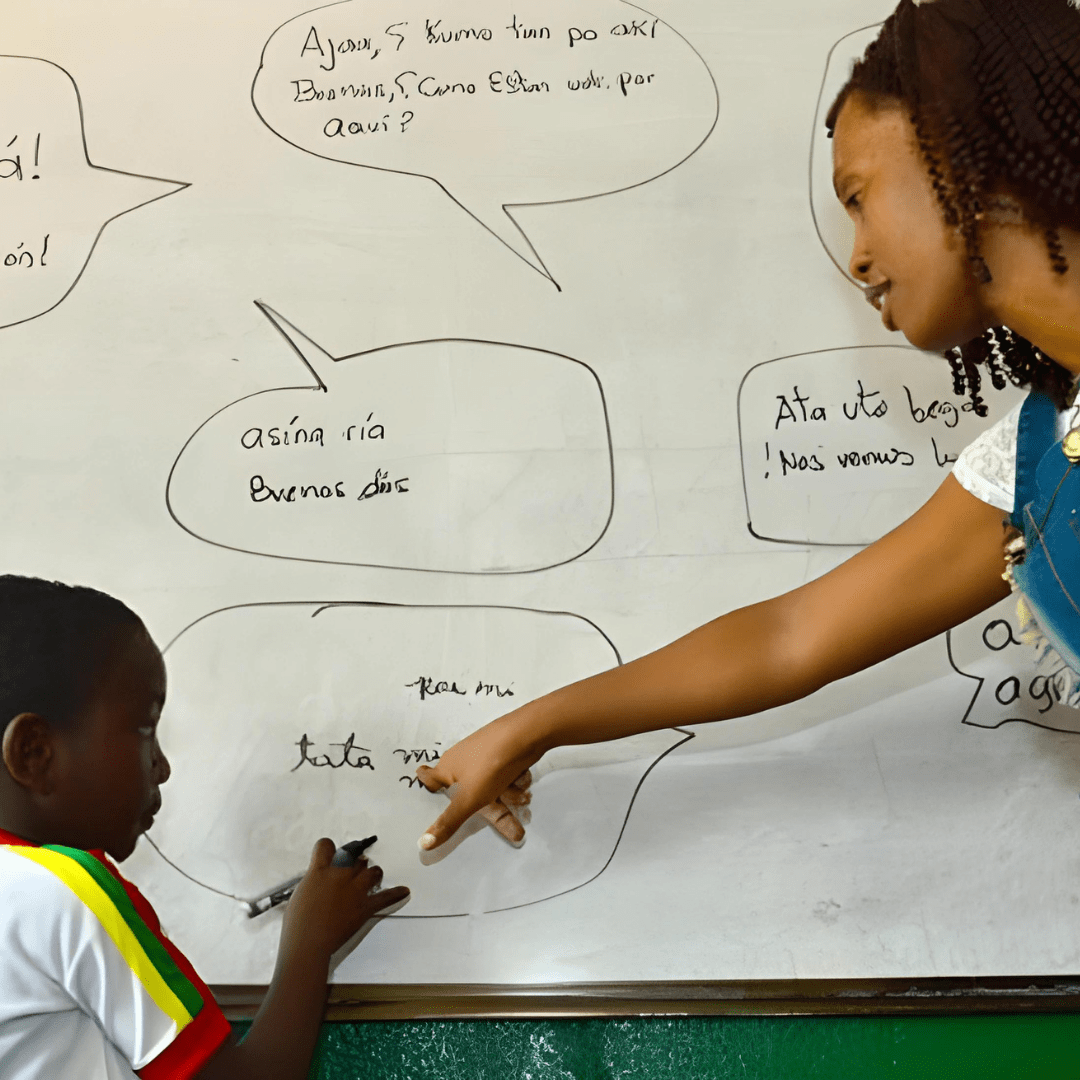

Creolophony in Latin America is a sociolinguistic phenomenon which, despite its diversity and richness, remains little-known. However, several types of Creole, such as Haitian, English, Martiniquan and Guadeloupean, as well as Maroon Creole, Palenquero, are spoken in these other Caribbean islands, where the official language is Spanish.

Spanish is becoming creolized and Creoles are tending to become Hispanicized. Like Spanglish, Fragnol or Portugnol, isn’t this linguistic cross-breeding marking the emergence of a new language: Kreygnol (Kreyñol)?

Creole languages were born of the continuous voluntary and, above all, forced migrations that converged in the Caribbean during the colonial era. These are composite languages,” says philosopher Édouard Glissant, “the result of contact between absolutely heterogeneous linguistic elements: Portuguese, French, English, Indian, Chinese and, above all, African. In this sense, the formerly enslaved African populations were its creators, and their descendants are today its main speakers.

Thanks to the multicultural turnaround experienced by the majority of the continent’s states, around 30% of Latin Americans now self-define as Afro-descendants. Among the latter, Creole speakers are loudly asserting their Caribbean identity and Creole languages. These include Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Panama and Colombia.

Haitian Creole in Cuba and the Dominican Republic

The roots of Creole in Cuba and the Dominican Republic are mainly due to the intra-Caribbean migration of the Haitian people. In Cuba, the presence of Haitians goes back so far that numerous studies have shown the fundamental contribution of Creole culture to the formation of the Cuban national identity. Following the uprisings linked to the Haitian War of Independence (1791-1804), many enslaved and free Haitians settled in southeastern Cuba, in the Guantanamera province.

A region that would later be continually irrigated by new waves of migration caused by the civil, economic and environmental crises that Haiti suffered during the 20th century and that continue to this day.

So, over several centuries, the Haitians brought with them their habits and customs: music, religion, philosophy, gastronomy and, in particular, their mother tongue.

Spoken by over 300,000 inhabitants of Haitian origin or descent, Creole is the second official language of Cuba, where “International Creole Day” is celebrated every year on October 28. One thing’s for sure, today more and more Cubans are learning or understanding it spontaneously. Even more interesting is the creation of the “Cuban patois”, a blend of Creole derived from Spanish, African languages and Haitian Creole, with a surprising abundance of African, Spanish and French words.

A similar, but much more confrontational, phenomenon is taking place in the Dominican Republic, where the Eurocentric national identity has historically been built on radical opposition to their neighbors.

This anti-Haitian sentiment has its roots in Haiti’s annexation of the Dominican Republic between 1822 and 1844, an abortive project to unify “Hispaniola”. Despite strong resistance from Spanish-speaking islanders, Haitian culture, both French-speaking and Creole-speaking, has left its cultural and linguistic mark over 22 years of domination, a mark that has only grown stronger with the incessant flow of Haitian migrants. As in Cuba, Creole is the second most widely spoken language in the Dominican Republic.

This is particularly true of the border area, known as La Raya (The Stingray), where, despite incessant intra-community conflict, mixed love affairs and local demand for cheap Haitian labor have fostered the emergence of a “Dominican kreygnol”.

West Indian Creole in Panama

In Panama’s Colón province, Creole culture abounds, imported by English-speaking and French-speaking “Afro-Caribbean” (Afro-Antilleans). Between 1851 and 1920, many Barbadians, Trinidadians and especially Jamaicans arrived in this region, along with entire families from Martinique and Guadeloupe, to work on the arduous construction of the inter-oceanic train and then the Panama Canal. If we’re talking more about the black male workforce, the migrant women who arrived in Panama without a contract also put in a remarkable amount of work.

As the fresco painted by artist Martanoemi Noriega for the Afro-Caribbean Museum illustrates, West Indian women, the forgotten figures in Panama’s official history, were true entrepreneurs.

They worked hard selling fruit and vegetables, Creole foods and domestic chores, creating an important economic synergy that guaranteed them a degree of independence. Although living conditions were precarious and often fatal for these West Indian migrants, Colón is one of the few places in the Latin American Caribbean where several Creole cultures converged simultaneously.

Today, it is home to the country’s largest black population, made up of the Afro-colonial (Afro-coloniales) population, i.e. the Afro-Panamanian population resulting from the Transatlantic Slave Trade, a sizeable English-speaking West Indian population and a smaller Martinican and Guadeloupean community deeply attached to its Creole roots. This original space where Spanish, English, French, but also French Creole and especially English flow together, called “Panamanian Creole”, is unique in its kind. The linguistic skills of the Afro-Caribbean people of Colón, who switch from one language to another with great ease, are remarkable and disconcerting.

Creoles of the Colombian Caribbean

Despite the linguistic colonialism of Spanish, two Creole languages are spoken in the insular and continental Caribbean of Colombia. In the archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina opposite Nicaragua, the Afro-Colombian populations, known as raizales, speak a Creole with an English lexical base very close to the Creoles of Panama, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Faced with a back-and-forth between English and Spanish colonization, the raizales have historically asserted the importance of safeguarding their mother tongue. This ancestral resistance has prevailed on this small, forgotten archipelago in the Caribbean. Since the 1990s, along with Spanish, Sanandresano Creole has been an official language, with English being the third language of this trilingual population.

Also in Colombia, an hour from Cartagena de Indias, Palenquero from San Basilio de Palenque is the only Spanish-based Creole language in the Americas.

It also includes words from Portuguese and the Kongo and Kimbundu languages spoken by the Bantu populations of Central Africa, bringing Palenquero closer to the Papiamento of the Dutch Antilles and the Surinamese Creole, Sranan. The relative isolation of this community has enabled the preservation of the Palenquero language, which has changed little from that spoken by 16th-century maroons.

As in the French and English West Indies, Creole culture is latent in the Latin American Caribbean.

In the complex history of the Caribbean, where the various European colonial projects took shape, this Creole culture blurs the apparent division between French-, English- and Spanish-speaking Caribbean peoples, showing us instead a cultural unity shared by their inhabitants.

Beyond music, gastronomy, spirituality and popular festivities such as carnivals, safeguarding Creole languages is undoubtedly one of the keystones of Caribbean identity.

Sara Candela