« Within the apparent disorder of the Caribbean, the discontinuous land masses, its colonial history, ethnics groups, languages, tradition and politics, there emerges an island of paradoxes repeating itself and giving shape to an unexpected and complex sociocultural archipelago »

Benitez Rojo in Sunset over the Caribbean.

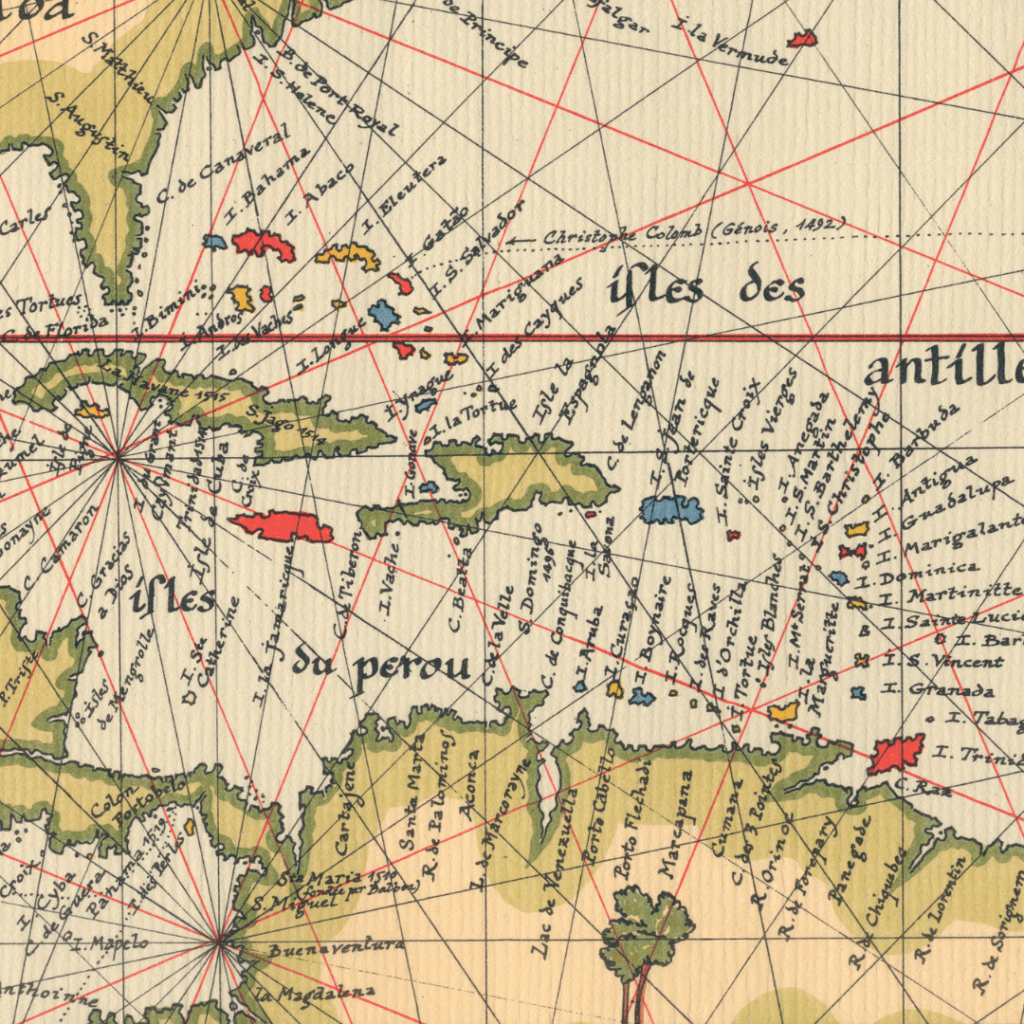

It is commonly accepted that Caribbean means all land, island or mainland around the Caribbean Sea. This definition has been extended, taking into account two historical factors: first, the settlement of this region by the Arawak People and secondly, the establishment of plantation society with the slave trade from Africa and post-emancipation indentureship from Asia. These movements of people have shaped multi-cultural societies and favored the emergence of new languages.

In an attempt to provide our readers with a more accurate definition to the word Caribbean, it is necessary to communicate the existence of a continuum in movements, ideas and theories and a chain of historical episodes which ended in the molding of fundamental concepts of Caribbean people, Caribbean identity and Caribbean culture.

The concepts of: Caribbean People, Caribbean identity, Caribbean culture

What are the values that we share which make us A Caribbean People? How do we express our sense of self and our sense of belonging? How do we embrace both a collective and individual perception of this oneness? What choices do we make in order to assert this Caribbean identity?

If Identity relates to the question: “Who are you?” What does it mean to be who you are? If the human being is said to be “ an essentially boundary-bound animal living in society”. Put differently, the Human is defined as a group-bound creature whose deep identity needs a sense of belonging which entails inclusion/exclusion relationship with others. The sense of belonging lies where individual identity meets communal identity. In this inclusive movement, mapipi, thinkers, novelists, poets, playwrights, activists and leaders define, describe, convey and transmit this sense of belonging. In our context, to paraphrase James Ferguson, they are “Makers of the Caribbean”.

MAPIPI. (Creole) Africanism from Angola highlands and Zimbabwe former Rhodésia.

The first stage of the initiation process was the nanni-nannan le nganga (creolized as ‘gangan’) meaning shaman, healed with plants.

The next stage, when this healer had reached the highest stage of intuitive knowledge (nganga of all ngangas), master healer, knowledge of absolute secrete of simples, he was called «mapipi ».

In Haiti, the mapipi is wa-gangan, king of all great empirical masters. In Martinique, a mapipi is someone who masters his Art and is the king among all, in his field.

Definitions of Caribbean identity

In the field of Eastern Caribbean integration, a study showed that there were five major constants in the answers about what gave a feeling of the sense of belonging in the region: the Caribbean Sea, the creole language, the English language, the archipelago, the Carifta Games.

« Cultural identity is not only a matter a ‘being’ but of ‘becoming’, ‘belonging as much to the future as it does to the past’. From This perspective, identities undergo constant transformation, transcending time and space. »

Stuart Hall in ‘Cultural Identity and Diaspora’, 1996

To elucidate the complexity of Caribbean societies three main theories have proved rather influential:

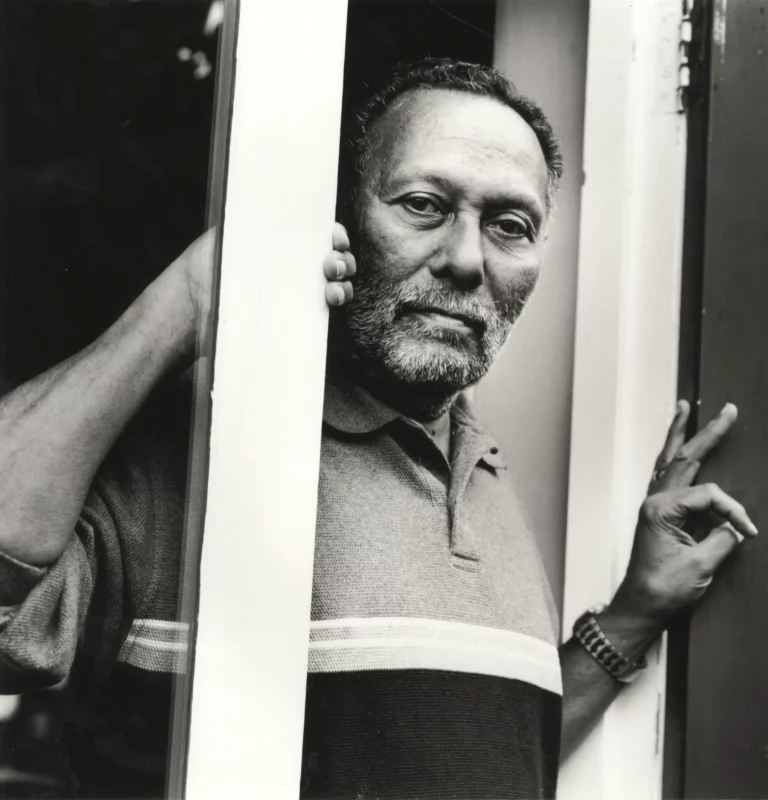

- The plantation model, initiated by Georges Beckford and taken up by Lloyd Best.

- The plural society model, (Smith , 1965)

- The creole society thesis by the Barbadian Kamau Brathwaite.

While the first two models lay the stress on cultural divisions and conflict the creole society model insists on cultural unity.

From Negritude to Creolization

Socio-historical conditions in the 1930’s contributed to a movement created by a Martinican intellectual elite. Negritude emerged from a specific context: It was a response to assimilation.

After emancipation, with massive access to schools and secondary education for black people a new society appeared. Consequently, soon, a middle-class of black doctors, teachers, lawyers, politicians appeared. Offering a new reading of colonial history, Cesaire destroyed the assertion of Africa as a single cultural unit. Tribal identities were restored. Africa is then defined as the craddle of Mankind. Cesaire’s Negritude movement strongly opposed the assimilation discourse, shedding the light on its barbarian project.

Fanon had developped the concept of colonial alienation, so powerful that it remained hidden until 2015 when his Ecrits sur l’aliénation et la liberté, were published by Editions de La Découverte.

As for Glissant, he produced the conceptual and notional scheme of assimilation as an ideology imposed on its colonized lands by France, based on the following assertions: Black people have no history; Africa has no civilization, no culture/Christianism is salvation from paganism/Thus colonizing is enlightening by bringing science, technology, culture, religion and morality/Colonization is a demand of Black people.

These Martinican thinkers contributed to the boosting of black consciousness and anti-imperialistic feelings in the entire Caribbean. In regards to these streams of thought, Garveyism, as an early protest movement in the English-speaking Caribbean and the USA, was very much different, since it was one of the first such movement to stem from the working class and the masses.

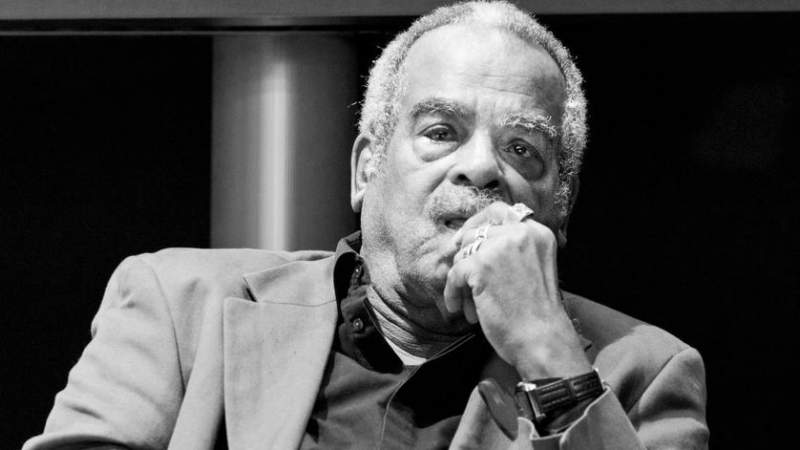

Anti- British and anti-American feelings were two factors which nurtured a regional feeling in the soon to be independent Caribbean. Anti-American sentiment can be interpreted as a desire to do away with colonial legacy and foreign influence. Eric Williams, in one of his famous lectures, Massa Day Done, laid the stress on the necessity to turn the page back on the master of slavery days.

A chain of facts gave impetus to regional integration and a sense of worth leading to a theoretical approach of Caribbean societies: Education of the people, the link between Caribbean people and their charismatic leaders: Williams, Bustamente, Bird, Cesaire, Damas, Manley’s Jamaica and Cuba in the 60’S and 70’s, the Grenada episode which marked the end of Britain’s influence in the region and surrender to the USA.

Creolization and creoleness

Since the 70’s, nationalism and local pride have become features of life in the Caribbean. Out of many one people, All ah we is one, are slogans fostering the idea of a creole culture that unites all Caribbean people.

If we consider Brathwaite’s concept of intercultural creolization: Its central argument is that the Europeans and Africans who settled in the New World have built a society which is neither European nor African but creole. Brathwaite identified « the expanding intermediate group », the coloured, who constitute the cement that helps to integrate society. Nevertheless, despite his insistence on cultural unity, Kamau Brathwaite have distinguished two groups in Jamaica: the Euro-creoles and the Afro-creoles. In response, Orlando Patterson argued that the process of creolization was not as developed during slavery, he proposed a different reading with the same two categories.

To understand creoleness, which is the state achieved after a process of creolization, an interior vision and self-acceptance are the necessary components for a reconciliation of the different parts of a divided self . These are the basic ideas conveyed by Jean Bernabe, Raphael Confiant, and Patrick Chamoiseau in In Praise of Creoleness: Eloge de la créolité, a bilingual essay written by these chantwels of the cause. The three thinkers consider that unconditional acceptance of our creoleness is the foundation of our culture.

« Creoleness is the interactionnal, transactionnal agregate of Caribbean, European, African, Asian and Levantine cultural éléments united on the same soil by the yoke of history »

In Praise of Creoleness: Eloge de la créolité (page 87)

Three centuries of common experience – in terms of languages, customs, cultures from different parts of the world – have forged a new humanity.

The following periphrases are used to describe creoleness: « It is the world diffracted been recomposed, a kaleidoscopic totality, the nontotalitarian consciousness of a preserved diversity”. The writers do not see their essay as a set of theories but as testimonies of creoleness. They consider that socioethnic relations ought to take place under the seal of common creoleness as it is the case in Seychelles for instance.

« We are not Africans, we are not Asians, we are not Europeans, we proclaim ourselves Creoles »

The cultural confrontation between all these peoples in the same environment forged creole culture. Creoleness englobes and complement Americanness (adaptation of Europeans, Africans and Asians to the New World). In some places Americanization, the encounter with America, has not evolved so as to achieve full creoleness.

To cut a long story short, the key elements allowing to achieve the stage of creoleness would be: fundamental orality, historical updating, thematics of existence, the burst into modernity and speech (choise and function of languages).

“Nation language is part of the creole continuum” says Kamau Brathwaite, as his poetry and theory is eavily influenced by this idea. Instead of merging two linguistic systems, Brathwaite’s nation language incorporates a much wider variety of idioms including Arawakian, Hindi, Chinese, and a number of African languages, which were various and generally shared semantics and syntactical features (Voice 6-7)

Given all the previously presented characteristics of Caribbean societies, what defines Caribbeanness? In a definition of our region as a relevant space for action – according to the geographer François Taglioni, what makes the Caribbean a coherent space for progress, if we rely on Stuart Hall, is “the double movement of containment and resistance”. It is the key which opens the door to describe any Caribbean human experience of which Carnival – and the sense of carnavalesque – seems to be one of the main features.

Dr Marie Françoise BERNARD

PhD in Caribbean studies

11 Responses